Few American filmmakers better exemplified the cynical, unsettled mood of the late 1960s and early 1970s than Mike Nichols.

In his legendary early films, Nichols specialized in jaundiced bewilderment. After all, what is the angst-ridden, post-college aimlessness of Benjamin Braddock (Dustin Hoffman) in The Graduate (1967) but a prelude to the marital viciousness of George and Martha (Richard Burton and Elizabeth Taylor) in Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? (1966) or the desultory conquests of on-the-make cads Jonathan and Sandy (Jack Nicholson and Art Garfunkel) in Carnal Knowledge (1971)?

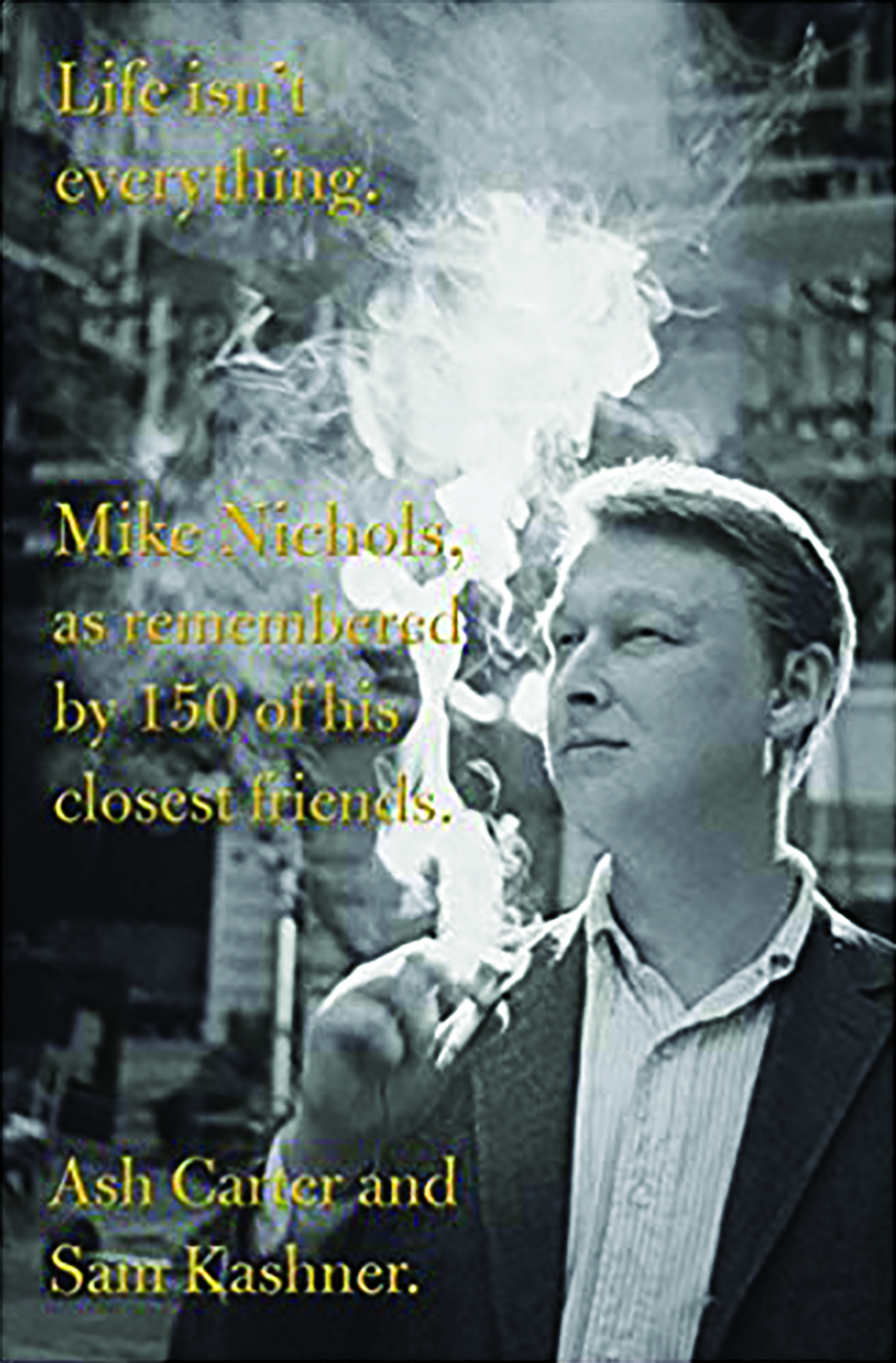

Yet, a new book about Nichols (1931-2014) reveals that he had relatively little in common with the world-weary protagonists of his early films. In a sparkling and well-organized oral history, authors Ash Carter and Sam Kashner spoke to (or quoted from existing interviews with) over 100 of the director’s colleagues and chums, including screenwriter Buck Henry, playwright Tony Kushner, and assorted friends ranging from Anjelica Huston to Rose Styron.

The verdict? The director led a life marked by unceasing activity, deep personal satisfaction, and genuine gratitude for a country that had showered him with fortune and glory.

A member of a prominent Jewish family in Berlin, Mikhail Igor Peschkowsky — not yet known as Mike Nichols — had his life first upended at the age of seven. In recognition of the threat posed by the Nazis, Nichols and his younger sibling Robert were shipped off to New York to live with their father. It wasn’t the only challenge he faced as a child: While still a toddler, he received a diagnosis of alopecia totalis, which resulted in the complete absence of hair. In adulthood, he donned a series of wigs. “They’d get slightly longer, and then he’d have a ‘haircut,’ and he’d go back to the shorter wig,” says actor Jeremy Irons, who starred in the director’s Broadway production of Harold Pinter’s Betrayal in 2013.

Yet between his status as a refugee and his baldness, Nichols had the freedom to construct a persona for himself from scratch. “I think Mike felt that life was very terrifying and that you had to have very good clothes and very good jokes in order to get through the day,” says playwright Jon Robin Baitz.

Nichols’s outsider sensibility manifested itself in the skits he conceived with his comedy partner Elaine May, many of which targeted traditional manners and mores. “This was the beginning of saying, I’m not afraid of the government, I’m not afraid of the institutions,” says Arthur Penn, who directed An Evening with Mike Nichols and Elaine May. And when Nichols turned to directing, he was drawn to astringent satires. He brought a kind of magisterial nihilism to his adaptation of Joseph Heller’s Catch-22 (1970), and his refusal to flinch from the dark implications of Carnal Knowledge led co-star Rita Moreno to praise him in rather backhanded terms: “Mike was a perfect person to direct that film. I think he had an icy kind of heart.”

Yet, Nichols disproved F. Scott Fitzgerald’s dictum that “there are no second acts in American lives.” In 1975, after The Fortune proved a box-office dud, Nichols took a temporary timeout from filmmaking. He rediscovered his audience-pleasing instincts, serving as the producer of the Broadway musical Annie.

When he returned to directing in the 1980s, Nichols was more charitable. “I started out, because of my personal experiences in early life, not liking or trusting people much,” he said in a 1991 interview in Film Comment. “But I now do like people, and by and large trust them in certain controlled circumstances.” Nichols also seemed to embrace the conventions of American life. Whereas The Graduate ends with Benjamin throwing a wedding ceremony into disarray, Heartburn (1986) opens with heroine Rachel (Meryl Streep) finding herself unexpectedly touched by the words read by a minister to a pair of soon-to-be-newlyweds. Best of all was Working Girl (1988), starring Melanie Griffith as a Staten Islander whose conquest of corporate New York is celebrated, not derided.

Projects such as the appealingly earnest melodrama Regarding Henry (1991) and the bracingly humane farce The Birdcage (1996) seemed to spring from the state of contentment Nichols enjoyed with his fourth and final wife, ABC broadcaster Diane Sawyer. “He was like a high school kid in love with the prom queen,” says writer Tom Fontana. Indeed, the tranquil happiness of Nichols’s 1988 marriage to Sawyer led him to shift the meaning of Elliot Loves, a play he directed soon after his marriage. According to production supervisor Peter Lawrence, “He made a play that was essentially about misogyny into a play about a character who was trying to leave the world of men and cross over into the world of women.”

Carter and Kashner take almost palpable pleasure in letting friends describe Nichols’s enjoyment of the fruits of his labors, including his imposing residences and horse-breeding hobby. “He was a great artist, but he was also great at civilized living,” says playwright Tom Stoppard. Adds friend Louise Grunwald, “Mike lived big-time. I say this in an admiring way. He wanted to see how everybody grand lived, took it all in, and liked the big life.’”

Peter Tonguette writes for many publications, including the Wall Street Journal, National Review, and Humanities.