Although the British visionary, poet, and artist William Blake (1757-1827) was moderately successful as an engraver, people thought his art was bizarre, that his poetry was gibberish, and that he was crazy.

Yet a 2019 retrospective at the Tate Britain sold about a quarter-million tickets and received rapturous reviews. The Guardian claimed that “he blows away Constable and Turner — and that’s with his writing hand tied behind his back.”

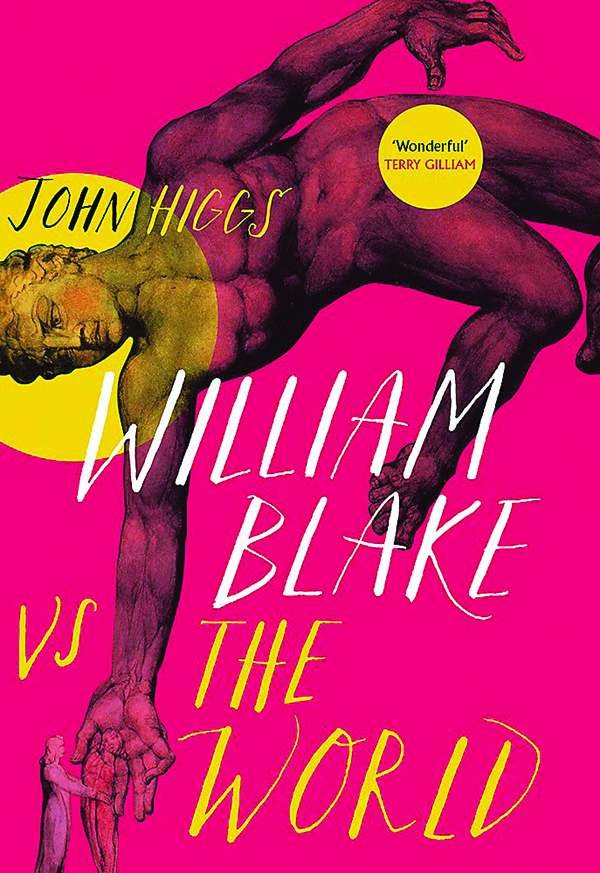

John Higgs’s latest book, William Blake vs. the World, tries to find the man behind the chatter and to understand whether he was a genius, a madman, or both.

Higgs displays Blake’s brilliance, noting the way his thought dovetailed with psychology, neuroscience, quantum mechanics, and chaos theory. He also shows his familiarity with work by William Shakespeare, Emanuel Swedenborg, Jacob Bohme, and others, at a time when most people were illiterate.

Yet Blake insisted he interacted with ghosts and spoke to Jesus, Milton, and Newton. He created his own cosmogony, crafting a mythology based on pre-Druidic beliefs. And he thought physical and spiritual entities were produced by human imagination. He also enjoyed sitting naked in his garden with his wife as a way to reenact life in Eden.

The third of six children, Blake exemplified middle child syndrome. He was independent-minded, he never fit in, and he was unable to agree wholeheartedly with anyone or anything.

His mother, Catherine, homeschooled him using the Bible as a tool and allowed him to daydream and wander through the countryside. Blake was captivated by Old Testament stories about people having visions and talking with angels. He was drawn to the Bible’s moral insights, its poems, stories, and literary style. His mother had belonged to the Moravian Church and imparted her spiritual sensibilities to him. Blake was grateful, saying, “Thank God I never was sent to school/to be Flogd into following the Style of a Fool.”

His father, a haberdasher, thought William had an overactive imagination. At 4, he told his parents he saw God’s face looking at him through the upstairs window. Later, he saw the prophet, Ezekiel, sitting under a tree. At 10, he saw a tree filled with angels. His father was ready to whip him for lying. Higgs suggests Blake’s visions were “neither lies nor objective truth.” They were a tricky blend of imagination and seeing with the mind’s eye.

His father arranged for him to study art and to serve a five-year apprenticeship before entering the Royal Academy drawing school. During this time, he examined the sculpture at Westminster Abbey and believed he had visions of the archangel Gabriel and of deceased monks processing and chanting hymns.

William favored his younger brother, Robert, who also had artistic tendencies. After Robert’s untimely death, William believed that his deceased brother spoke to him and was a source of his inspiration, helping him discover the technique of “relief etching,” which allowed him to produce the illuminated books for which he became known. At this time, Blake found the mystical philosophy of Swedenborg, whose visions and occult beliefs about the afterlife and dead people communicating with the living deeply affected him.

Blake wrote about his visions, illustrated them, and made them the subjects of mythologies, prophecies, biblical dramas, biographies, and poetry. He encouraged people to open their eyes: “If the doors of perception were cleansed,” he wrote, “everything would appear to man as it is, infinite.” (The Doors named their rock group after Blake’s line.) His most anthologized poems come from his book, Songs of Innocence and of Experience, the title page of which noted the book’s aim, to show “two contrary states of the human soul,” emphasizing Blake’s idea of the generative power of opposites especially as seen in the two poems “The Lamb” and “The Tyger.”

He married Catherine Boucher, whom he taught to read and write. She became his assistant. Although most of his contemporaries deprecated his art, she believed in him.

He believed in a “Sky God,” which he portrayed in the engraving “The Ancient of Days,” and which graces the cover of this book’s U.S. edition. Many scholars see this image as a visualization of Yahweh, the Hebrew father God who in Blake’s rendition holds a compass as he creates the Earth.

Higgs disagrees, saying that even though the figure looks like God, he is actually an ensnaring divinity of reason and law called Urizen. Higgs also questions Blake’s Christianity, categorizing him as a divine humanist who believed that God exists as an entity within each person.

During Blake’s last years, the Romantic poets embraced his work. William Wordsworth thought him a madman but said he was more interested in Blake’s madness than “the sanity of [poets such as] Lord Byron and Walter Scott.” Blake disliked Wordsworth’s love of nature, saying nature was demonic. Blake was intrigued by Samuel Taylor Coleridge, whose poetic imagination was close to his own.

Considered the earliest Romantic poet and the first Modernist, Blake was ahead of his time. When he died at 69, Blake was a pauper and his work was generally unappreciated. Blake had one solo exhibit. That was held in a room above his brother’s haberdashery shop. Robert Hunt, the only person to review the show, panned it, calling Blake an “unfortunate lunatic” and his creations “a farrago of nonsense, unintelligibleness, and egregious vanity, the wild effusions of a distempered brain.”

Blake described his writing as a golden string that would lead readers to experience his visions and ascend to “Heaven’s gate/Built in Jerusalem’s wall.” Those words, from his epic poem “Jerusalem,” are on his grave marker at Bunhill Fields, London, his final resting place.

This is Higgs’s seventh book and his second one on Blake. In it, he develops ideas presented in his earlier, 96-page work, William Blake Now: Why He Matters More Than Ever.

This second biography, which came out in England in 2021 with a U.S. edition in 2022, draws from numerous sources including Alexander Gilchrist’s Life of William Blake, the earliest biography, and Peter Ackroyd’s Blake, a recent bestseller. Higgs’s book is chatty, somewhat wordy, and uses a few too many colloquialisms. But that’s a quibble in a book that tries to understand the mind of any person, especially one like Blake’s.

This difficult but rewarding biography suggests that Blake would have appreciated Walt Whitman’s long, lapping lines of poetry, agreed with Ralph Waldo Emerson’s ideas concerning self-reliance and individualism, and championed free verse. (Higgs doesn’t mention the 1913 Armory Show in New York, but one can easily envision Blake admiring Marcel Duchamp’s “Nude Descending a Staircase.”). Poets such as E. E. Cummings and artists such as Maurice Sendak were inspired by Blake. So were rock groups including the Beatles, the Doors, and many others who put his poems to music thereby acknowledging his virtuosity and making him at long last a force to be reckoned with.

Diane Scharper has written seven books. She teaches memoir and poetry for the Johns Hopkins University Osher program.