When Edward Harrison “Ed” Crane III walked into an unusual political meeting at the Denver Radisson Hotel in 1972, he didn’t know quite what he was in for. Crane, who died of a heart attack Feb. 10, age 81, quipped that while he understood “as a libertarian” that it might be “imperative to be tolerant of alternative lifestyles,” it wasn’t until he stepped into the hotel’s convention hall that he got some sense of just “how many alternatives there were.”

Among the cliques represented at the Radisson, Crane would find “goldbugs, left-anarchists, hidebound Objectivists, and even to his surprise a fair number of free-market rightists disillusioned by [President Richard] Nixon on wage and price controls, but still foursquare for fighting Vietnam to certain victory,” writes author Brian Doherty in his book Radicals for Capitalism: A Freewheeling History of the Modern American Libertarian Movement.

The meeting was the first national convention of the Libertarian Party. Crane, a University of California, Berkeley-educated financial manager in his late 20s, was in a small room with maybe eight others when the first LP platform was drafted. After that, he was given the title of campaign manager for the first vice presidential nominee, Tonie Nathan, since the party needed to put someone’s name on that line to satisfy election paperwork requirements.

The LP didn’t garner many popular votes for president in 1972: fewer than 4,000. Yet it did make headlines in early 1973 when one member of a state delegation to the Electoral College, who was pledged to vote for Nixon, became what is known as a “faithless elector.” He peeled one vote off Nixon’s 49-state rout of George McGovern and instead voted for the LP ticket of John Hospers and Nathan.

Crane ran for and received the LP chairmanship in 1974. For a time, when people called the LP national party number, it rang through to a phone at his desk at the San Francisco firm where he worked. He soon took what amounted to a large pay cut and moved to Washington to take over party operations full-time.

Crane made a number of moves to increase the reach of the LP and the pro-market, antimilitarist, small-government ideas it stood for. He took the party’s newsletter, the LP News, and mailed it out for free to any remotely sympathetic mailing list, crisscrossed the country trying to organize state parties, and worked to secure ballot access. As an LP strategist, Crane struck gold two or three times.

The first gold strike was recruiting Ed Clark, a New York attorney who had relocated to California, to run for governor in 1978. He pulled an impressive number of votes: 377,960, or 5.46%. The second strike was attracting the attention and patronage of a pair of billionaires, brothers Charles and David Koch of Koch Industries.

Crane combined these two in the 1980 presidential campaign. The LP ticket had Clark as the presidential candidate and David Koch for vice president. The Supreme Court’s Buckley v. Valeo decision left one important campaign-finance loophole open: A candidate could spend as much of their own money as they wanted on their own campaign. David Koch allowed the LP to open the spigot.

The LP presidential ticket then garnered 921,128 votes. It also secured guaranteed ballot access in all 50 states. But at the 1984 convention, Crane’s and the Kochs’ preferred candidate lost the nomination by one vote after a concerted effort by many LP members to oppose anyone they backed. Consequently, “Crane and his crew, along with the Kochs and all their money, departed the LP after their candidate lost, never to return,” Doherty writes.

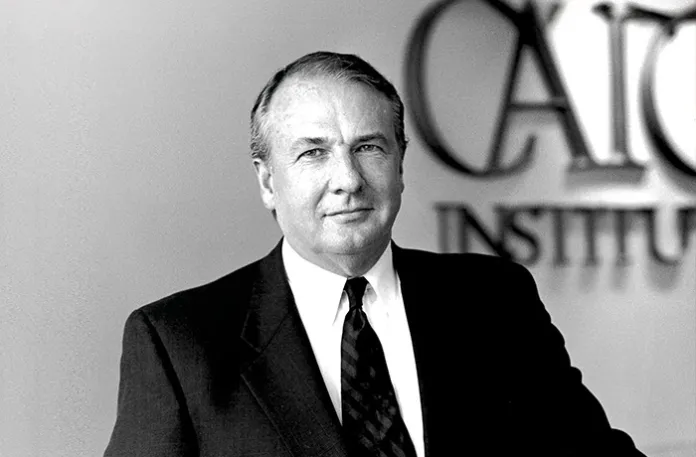

Along the way, Crane founded the Cato Institute. The think tank was created in San Francisco, then exported to D.C.

As it developed, Crane’s Cato, where I worked for a few years in the early 2000s, was meant to be the serious, rigorous, dressed-up, professional face of libertarianism, which was considered a radical philosophy of government in the post-New Deal, post-Great Society United States. Cato scholars argued for ending the drug war, legalizing gay marriage, shrinking the budget and mission of the U.S. military, normalizing large-scale immigration, voucherizing education, cutting discretionary spending, cutting taxes, and 401(k)-izing Social Security.

Crane ran Cato from its founding until a 2012 rift with Charles Koch. “If I had been smarter, more mature, I would have said, ‘Okay, Charles, we’ll work something out—you can take my spot,’” Crane told the Washingtonian magazine at the time. That rare admission of fault failed to smooth things over.

MAGAZINE — IT’S THE PRICES, STUPID: THE BIG CHALLENGES THAT LIE AHEAD FOR TRUMP AND THE GOP

Crane raised money for libertarian-leaning candidates with a now-defunct organization called Purple PAC. It reached over $3 million in the 2015-2016 campaign, according to Federal Election Commission filings, but then petered out.

Crane is survived by his wife, Kristina, and their three children, as well as by a robust Cato Institute. The house that Crane built is likely to stand for some time.

Jeremy Lott is the author of several books, most recently The Three Feral Pigs and the Vegan Wolf.