When people ask me why I voted for John McAfee in the 2020 election, I simply respond that I wanted a return to normalcy. Am I trolling, or joking? That’s up to the listener because that’s the way McAfee would have wanted it. He never let everyone in on the act completely.

McAfee, the globe-trotting, flamboyantly rogueish antivirus software mogul who spent the last chapter of his life making delightfully offensive video messages while apparently on the run in an archipelago of villas and Bond villain lairs, died of a reported suicide in June 2021 while incarcerated in a Barcelona prison. The internet and social media went full “Epstein didn’t kill himself” over McAfee’s sudden demise. He would have loved the troll value of his own death. McAfee has been the subject of several documentaries, news segments on web outlets such as Vice, and even the biographical topic of a fictionalized film. That project had everyone from Johnny Depp to Michael Keaton attached to play the former software virus mogul and would no doubt blur the boundaries between reality and fiction, much like McAfee himself did.

When I interviewed him for my own podcast in November 2019, we were on a Zoom conference call, and his room was wallpapered from ceiling to floor in silver foil. He claimed he was somewhere in the world evading CIA kidnapping strike teams. I just went along with it, even if it wasn’t true because who cares? McAfee’s stories were always more interesting to roll with than to question like in a 60 Minutes interview. He fell somewhere between genius and supervillain, extremely educated, well read, and obviously charming. His love for his wife Janice was apparent. McAfee was a warrior poet but also the Joker.

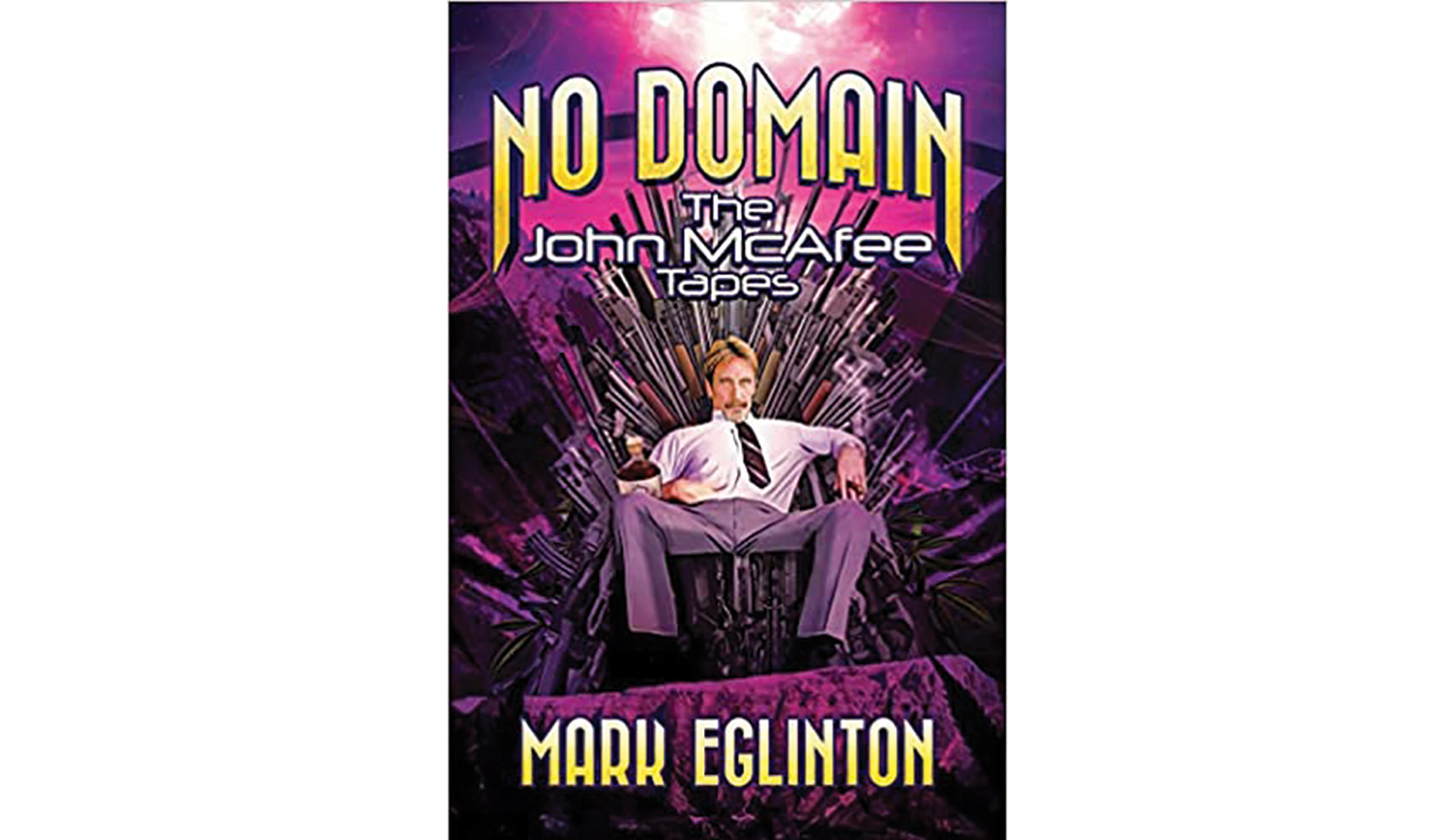

Author Mark Eglinton contacted McAfee the same way I did: on Twitter. One of McAfee’s best qualities was his eagerness to talk. He’d talk to anyone, for the most part. Eglinton has now authored a book based on his conversations with McAfee titled No Domain: The John McAfee Tapes. Because the book is based largely on McAfee’s own stories, the book itself dances between truth and fiction, like McAfee is “Verbal” Kint sitting in a police station looking around the room and giving police interrogators pieces of information of things only he knows are true or false.

“With the working relationship seemingly unshakeable, things got really f***ing weird,” Eglinton tells us, explaining how a complete collaborative effort with McAfee was going to be impossible. McAfee made unusual demands for payment. For example, he’d accept only cryptocurrency in order to avoid an actual address and banking information. It almost tanked the process. “‘Publishing seems to be the only business in the entire world that cannot use cryptocurrency. F*** them,’ was his terse sign-off to me one evening.” Eglinton got a firsthand experience of McAfee’s inherent distrust of the media, the government, and in some cases, even his own neighbors. For Eglinton, all the mistrust and mind games leave the biographer trying to debunk much of the mythology around McAfee.

Once the scene is set, the book becomes largely a series of interviews conducted over several months about some of the more publicized events in McAfee’s life, from the software that made his fortune to the murder in Belize that led to his life on the margins. Eglinton makes an earnest effort to extract as much as he can from McAfee over the course of the material and of course often runs into the Hannibal Lecter-type wall McAfee spent years building around himself and his own image.

For instance, when Eglinton presses McAfee on his supposed CIA connections that reveal the real reasons behind the Iraq War, McAfee replies, “I rarely discuss this kind of stuff, but lately, I have had to because people just think I’m a f***ing conspiracy theorist. But I know people in the CIA. One of them still emails me every other day, and we physically talk once a week.” It’s just cryptic enough to draw the reader into his own created world. Is it true? Who cares? He makes it sound real and interesting. It makes it hard to discern the more personal stories of McAfee, the things that aren’t about the CIA chasing him across the globe or his cultish compound in Boulder, Colorado.

Eglinton attempts to dig into his family history, only to find McAfee again spinning yarns. When pressed about his father and possible abuse, McAfee again gives a visual narrative out of a Terrence Malick film.

“By the time I was twelve, I could tell by the sound my father’s shoes made when he walked across the hall what kind of mood he was in. Accordingly, I’d either be jovial with him, or I’d just pick up my books and go to my room. I instinctively knew which to do and when. And my point is that, once you’ve learned how to read one person, you definitely notice how valuable that ability is as a tool in all human relationships. I was never the biggest, the strongest, or the fastest kid in my neighborhood. But I was the boss of every f***ing neighborhood I ever lived in because I became adept at reading people and treating them accordingly.” It’s like a story that could have come right out of the first 15 minutes of Goodfellas.

We can take stock of No Domain’s limitations and its successes, but criticizing it is something of a fool’s errand. This is the only possible book that could have been written about John McAfee. An autobiography, while interesting, would reveal no real personal information and would likely be more grand half-fictions meant to entertain the room, and no more critical investigation would have turned up anything or resulted in cooperation. With Eglinton respectfully pressing back and at times very skeptical on what is true or not true, he puts McAfee in the chair and under the spotlight. It is an easy read about an incredibly complex character, and one we might never see again in this world, which is a shame, because now, I have to search for another candidate for 2024.

Stephen L. Miller is the host of the Versus Media Podcast on Patreon and has written for National Review, the New York Post, and is a contributing editor for the Spectator. Find him on Twitter @redsteeze.