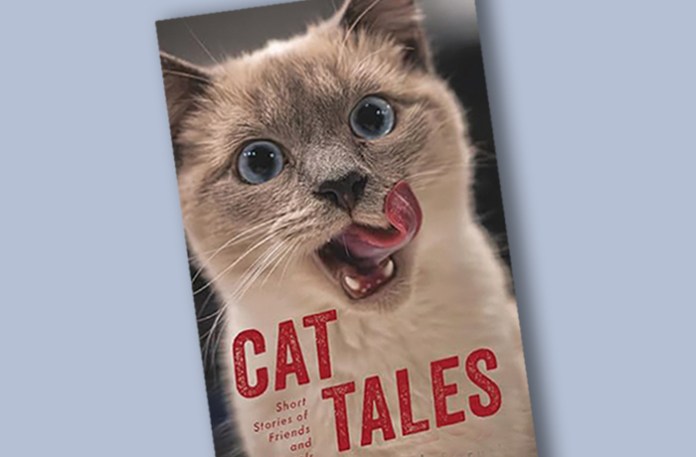

The following is adapted from Jack Baruth’s book, Cat Tales.

I don’t know when she made her choice. All my first glimpses of her were indistinct. A mottled white streak across a field, briefly spotlit by my truck’s high beams. One eye and ear peeking around the corner of my barn. Over the course of a month or so, as the weather improved, these fractions resolved into a complete cat. She’d low-crawl up to the outdoor food dishes when the others had finished eating, sneaking small bites as she shuddered and looked around for danger. Young, small, lean, always in motion, and absolutely terrified of people.

But not all people, as it turns out. On Friday, our daughter easily captured what turned out to be an obviously female teenager, mostly white with grey head and back patches in the bicolor pattern known as “harlequin.” Where did she come from?

The first clue: hearing a new dog barking at the neighbor’s house. Some new woman started coming by about a month ago. Now she lives there. This disturbs my middle-class sensibilities. Anyone who moves in after just a couple months of dating, or who moves someone into their house after just a couple months of dating …

Perhaps our new bicolor girl had been a semi-tame cat at my neighbor’s house, only to be discarded in favor of this woman and her dog. It would explain both the scratches on the cat’s nose and her fondness for human companionship. But there was a bigger reason for the behavior, one that was obvious once I picked her up and held her. She was pregnant, hard-bellied, and showing a bowling-pin plan view as she ran past me to join the other cats at breakfast.

“Thousands of dollars,” my wife sighed, with a despondent expression that would have done justice to Joe “Tiger King” Exotic. “And where will they go? We have eight indoor cats already.” The obvious thing to do: Head to the vet for walk-in hours Monday morning and get it handled.

First, however, the cat had to be named. I already had ideas about that. The previous week, I’d been given a lovely porcelain cat. It’s not important why I got it — okay, okay, you twisted my arm, I’ll tell you, I bought a new Spring Drive watch in Ginza, utterly silent, I’ll have it paid off in 2035, they gave me the cat out of pity, I think — but the pattern and color of the porcelain kitty kinda-sorta resembled my new tenant. So I named her “Neko”, which is simply Japanese for “cat”.

Neko and I drove over to the vet and waited in the parking lot until it was our turn, which took about three hours. Monday morning is rush hour there. When we got in, I explained the provenance of our new friend, and what I wanted: an abortion, followed by sterilization. “Well, I don’t want it,” I clarified to our lovely rural veterinarian, “but I have eight indoor cats and I’m feeding another dozen-plus outside. Sixty cans of cat food a month. Forty-five pounds of dry food. It has the scale of an operation by the now-deprecated USAID. There has to be a limit.”

“I understand,” she replied. “I’ll take the kittens out. I don’t like doing it, but … the shelters here are full. Come back at three o’clock and get her. I’ll take it from here.” To my credit, I walked out with a placid expression and didn’t shed the first tear until I put my seatbelt on. Then I shuddered with my head in my hands for ten long minutes. I thought about last fall’s kittens, and how much poorer my life would be without them. I thought about Neko, who had come to our front porch because she was pregnant and hungry and perhaps newly homeless. Who was I to command this? What right did I have? Just because I “know better” than she does?

Then, as always, my thoughts turned to the moment I first saw my premature son in his plastic box at the NICU. Before he could talk or crawl or even breathe. When he was meat. As these kittens were. As I often feel myself to be, nowadays. No soul, no particular worth, and an expiration date in the near future.

My wife called me as I was on the way to a self-pitying lunch. “I didn’t realize you were taking her there for an abortion. I thought you were just going to get an X-ray so we could see how many kittens there would be… and we could make a plan from there.”

“But the plan,” I replied, “was almost certain to be an abortion. So why wait?” There was a long pause on the other end of the phone.

“I don’t support this.” I brought my raggedy old Lexus to a halt on a side street and squeezed the unyielding wood of the steering wheel beneath my palms. Took a breath. Decided once more.

“Neither do I.”

“Then call the vet, before it’s too late. Get off the phone with me, and call the vet.” I immediately envisioned Neko being already sliced stem to stern, saw the black eyes of each kitten opening for a first and final time as they were spilled out onto a blood-soaked table beneath a flashing scalpel. Behind me, someone’s minivan was honking.

“Tell the doctor,” I stammered into my phone, “Tell her I’ve changed my mind. Just do an X-ray, do an exam, vaccinations. I’ll have the kittens, and bring them back for spaying when it’s time.” The assistant paused. This is a rural practice, and she’d seen I was driving a $4,500 piece of junk with a broken taillight.

“There’s some cost to that… I just want you to be prepared.”

“Lady,” I replied, “I’m wearing a Spring Drive. I can afford to spay a few cats.” After lunch I went to pick Neko up and talk to the vet. She took me back to her janitorial closet, which doubled as a makeshift X-ray room, and showed me the spines and silhouettes of a feline trio in Neko’s belly.

“She’s three weeks out. The kittens aren’t fully formed, but they’re close.” She paused for effect. “I’m glad you didn’t ask me to do the procedure.” She smiled, radiantly. “Bring Mom back afterwards. We’ll fix her and give her the rest of the shots. Then bring the kittens. They don’t have to live indoors forever. I know how you look after your outdoor cats. They will be just fine.”

On the way home, Neko mewed and pushed her injured nose at me through the bars of the carrier. I opened the top and let her escape to enjoy the drive, unaware, surely, that I’d made the decision twice, two different ways. And she would have had to live with my choice, whatever it had been. Beneath my hand, her tiny skull vibrated with audible and outsized purring.

MAMET’S WORRIED SIGH OF RELIEF

“As a self-identified redneck from a red state,” I told her, “I disapprove of border-crossers such as yourself who expect meals, housing, and free healthcare from the system. However, I do feel you have a legitimate claim to asylum. Our neighbor is a headcase and this new broad of his looks dirty from a distance. Also, I like your snuggly little face.” Neko didn’t look reassured. Something more effective was called for here, and I thought about the old “Feel, Felt, Found” technique from back in 1994 when I was selling cars, badly. “Neko, you might not feel that you’re ready to be a parent. You might feel that you haven’t lived enough, haven’t had time to do everything you want to do. Now, I felt the same way, when I realized my first wife was pregnant. But what I found is that parenting is more than just an inconvenience, and children are more than a distraction. This is why we’re here. It’s our purpose. You and I will get through it, and at the end you’ll have someone to love, someone to live for. Just like I do.”

Once home, I went into my office to sit in the Eames and read before beginning my second-shift day in earnest. After half an hour or so, Neko came in and climbed into my lap as if we’d known each other our whole lives, as if today’s decision had been the only obvious or even possible one. It gave me some sympathy for my idiot neighbor. Maybe it’s not so awful to fall in love and want that person to be with you immediately, regardless of propriety or common sense. Maybe it’s just a matter of being someone who always says yes to an opportunity, instead of someone who always says maybe, or well, that’s not realistic. Maybe it doesn’t matter how quickly or even why you made your choice, only that you made it, and that you can live with it. “Oh, yay…” I muttered to Neko, flipping the New York tabloid back open. “More stories about migrants and borders.” She mewed, perhaps in sympathy, or perhaps to chastise me for its absence in my previous statement. Then we settled down to the task of reading, as the Spring Drive silently measured the minutes away. In this way we prepared for the lives, and the life, that would result from my choices.

Jack Baruth was born in Brooklyn, New York, and lives in Ohio. He is a pro-am race car driver, a former columnist for Road and Track and Hagerty magazines, and writer of the Avoidable Contact Forever newsletter.